The most obvious and most important way of measuring success and progress on the ACT or SAT is through the score on an official sitting of the SAT or ACT. My ultimate goal when I work with my students is always that they achieve high scores on their tests, and this is almost always the ultimate goal of my students and their parents as well. However, I find it to be counter-productive for students to be excessively focused on their final scores both during preparation for their tests and, to an even greater extent, while taking their tests. I assign many sections of retired official practice tests to my students to do for homework between our sessions. When they do these sections, my primary intention is for them to practice the strategies that we worked on together during the session. If students are excessively concerned about how they are going to score as they do practice sections, they are going to be less inclined to practice new skills, to take risks, and to learn from the process. Some students become very locked into unproductive patterns when they are tense about how they are going to score on each individual practice section. This is not to say that I don’t pay any attention to the scores on practice sections. In fact, I track how my students score on practice sections over time, and I like to see a gradual trend towards improvement. However, I’m unconcerned about dips up and down from week to week as we practice and experiment to optimize the strategies for that student. I sometimes tell students that every thought that they have about their scores as they take their tests is one less thought that goes towards doing what they need to do in order to get high scores. In other words, while students are taking the SAT or ACT, giving any attention at all to how they think they’re going to score is at best distracting from actually using their strategies and answering questions well and efficiently. At worst, it’s anxiety-inducing. I also tell students that if they are going to think about any score, imagine that I am standing behind them scoring them on how well they execute the strategies that we perfected. I ask them to pay attention to executing their taking of the test so well that I would give them a perfect score for execution. A perfect score on execution is the means to a high score on the SAT or ACT.

0 Comments

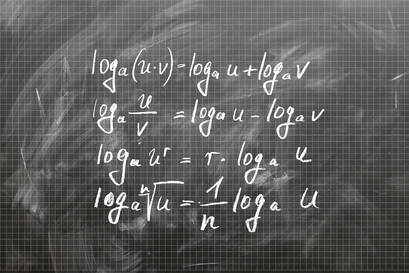

With proper training, taking the SAT can With proper training, taking the SAT canbe an experience like this. This is the third part of three in my series of posts on the Three Pillars for Success on the ACT and SAT. If you haven't read the first and second parts, I recommend doing so before reading this one. (Click here to read the first part and here to read the second part.) Most students experience incredible pressure during the days and hours leading up to their tests and while they take their SAT or ACT. Many students see these tests as the most important tests that they have ever taken. Many are painfully aware that whether their college dreams become realities depends on how they perform during just a few short hours. There are a few people who think better under pressure, who become more clear-headed and calm, but these people are rare. For most people, pressure to perform creates anxiety. Some students experience a little bit of anxiety around the SAT or ACT and some experience a lot. When we feel anxiety, our bodies go into fight-or-flight reactions. Fight-or-flight reactions improve our abilities to run from dangerous situations or to fight off attackers, but fight-or-flight reactions do not help us to think clearly and calmly or to sit still and concentrate. In fact, anxiety suppresses the frontal parts of the brain that are involved with rational thought, concentration, and short-term memory. These are not conducive to scoring well on the SAT or ACT. The third pillar for succeeding on the ACT or SAT is being calm, collected, and confident on test day. Whether a student has a good day or a bad day when she takes the test depends significantly on her mental state going into and during the test. Even if she has great strategies in place, knows the content really well, and has been scoring well on practice tests, if she is so anxious when she takes the test that she forgets to use her strategies and can't even think clearly, she's unlikely to do nearly as well as she's capable of doing or as well as she did on practice tests. If a student only sleeps for two hours the night before the test because he's anxious, he is unlikely to score at his best either. Fortunately, there is a lot that students can do in the weeks, days, and hours before their tests and during their tests to reduce their anxieties and perform at their best. With all students, I work at least little bit on emotional awareness and management of their emotional states, because even the performance of those rare people who do best under pressure can improve with the techniques that I teach. With students for whom anxiety is a particular issue, I work on techniques for emotional awareness and management a lot. The amount of time that I spend working on this with a student depends entirely on how much anxiety affects this student’s well-being leading up to the test and performance during the test. Students being at their best on test days is not a wild card; calm, collected, and confident emotional states while taking their tests is something that students can learn to cultivate.  This is the second part of three in my series on the Three Pillars of Success for the ACT and SAT. (Click here to read the first part of the series.) In the first part, I discussed how mastering effective strategies is the most important pillar for success on the SAT and ACT. The next pillar that I will discuss is content. What I mean by content is how well students know the math concepts, how well they read, how well they understand graphs and tables for the science section of the ACT, and how well they know grammar and punctuation. Content is what the ACT and SAT are most explicitly testing. In fact, the makers of the SAT and ACT tend to imply that knowing the content is all that is required to do well on these tests. My experience is that this is simply not true. As I discussed in the last post, it's very possible for students to be highly skilled in math but still not score well because they haven’t learned the skill set of taking standardized tests. Don’t get me wrong. Knowing the content well is extremely important as a pillar. It's just not sufficient without knowing great strategies as well. There is a lot that students can do in relatively short periods of time to improve how well they know the content of the SAT and ACT. If students have more time to study, then they can learn and improve their knowledge and abilities with the content even further. While students can improve their skills with and knowledge of the content a great deal, especially if they have the guidance of a skilled teacher, I have to acknowledge that there are some limitations in terms of how much students can improve in this pillar. For example, by the time students are taking the SAT or ACT, they have been learning to read for many years. If they are weak readers at this point, while it is certainly possible for them to improve their reading skills considerably in a few months, and while strategies can help compensate to a certain extent, they are also unlikely to become masterful readers and get top scores on the reading section as a result of studying for a few months, or even for a year. On the other hand, the grammar and punctuation rules that students need to know to do well on the English section are completely learnable by most everybody in a relatively short period of time. Once I have worked on strategies with my students, my next priority is to assess what content they already know well and what content they don't yet know well so that we can focus on their weaker areas. To summarize, a lot of improvement of students' scores is possible through studying the content of the SAT and ACT if students have great strategies in place as well. While some improvement in knowing the content is possible in a relatively short period of time, when students have a longer period of time to study, they can make a lot more progress with learning content well and truly maximize their scores. Click here to read about the third pillar for success on the SAT or ACT.  I have tutored hundreds of students over the years to help them maximize their scores on the SAT and ACT, and through all of this work with students, something has become clear to me: test preparation must include three pillars in order to be effective. All three pillars are critical and each must be strongly in place for students to succeed at scoring their best. Sadly, very few test prep tutors, classes, or books effectively cover all three pillars. This is the first blog post in a series of three in which I will discuss each of these three pillars. The first pillar that I'm going to discuss is the one that I consider to be by far the most important in determining students' scores and also the one that tends to be most neglected by most test prep tutors, classes, and books. This pillar is strategies. By strategies, I am referring to the ways students manage their time and what they do and are aware of as they take their tests. I'm not referring to “test-taking tricks”, which don't tend to be very effective on modern versions of the SAT and ACT, even though many books still focus on teaching such tricks. In order for students to maximize their scores on the SAT and ACT, mastering great test-taking strategies is critical. These are a few examples of what I mean by strategies:

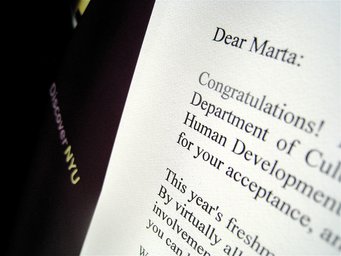

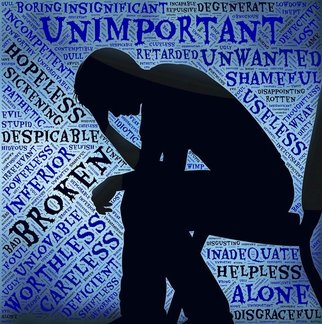

Most students find standardized tests to be quite different from the tests that they take in school. There really is a skill set for taking standardized tests that is very learnable and that most students haven't learned when they begin studying for the SAT or ACT. Students who are trying to do well on standardized tests without learning the skill set for doing so could be compared to people trying to pitch in baseball with their legs tied together: they'll probably manage to throw the ball somewhere near the plate with their legs tied together, but the pitches are unlikely to be very good. Here's an example of how not having solid strategies in place can harm a student's score. I recently worked with a student for the ACT who was extremely strong in math. She knew all the math concepts. She rarely made computational mistakes. She was great at finding creative solutions to difficult math problems. Before she worked with me and learned strategies, her issue in the math section of the ACT was misreading questions. Unlike most math questions on tests that she (and almost all students) take in school, most math questions on the ACT have a paragraph that she had to read and understand before she could do any actual math. Even though she knew all the math concepts and was good at solving math problems, she kept misreading questions and thus effectively solved a different math question than what was being asked. As a result of misreading a few questions incorrectly, this student ended up with a very mediocre score on the math section, even though she was truly skilled at math. Using the strategies I taught her, this student was able to improve her ACT score considerably. The issue that this student had is a very common one, and not just on the math sections. In fact, I believe that the majority of students who take the ACT or SAT score much lower than they are capable of scoring simply because their strategies are far from optimal, if they have any strategies at all. Without good strategies, they end up with scores that do not reflect their true academic strengths. Ideally, by the time students take their tests, the strategies that they use for each section and for all the question types will be habitual. They shouldn't even need to think about how to approach sections or how to manage their time well. These aspects should be automatic. The good news is that if students get solid guidance on strategies and they do a good amount of practice with these strategies, it is absolutely possible for students to have mastered their strategies by the time they take the ACT or SAT. My experience is that most standardized test tutors and class teachers do not focus on strategies or even know effective strategies very well. I once worked with a student who had worked with a tutor from one of the major test prep companies weekly for more than a year. He read well and knew the math well, but he had practically no strategies. He had taken the ACT three times over the course of that previous year, and he scored exactly the same each of those times. I worked with this student for only four ninety minute sessions, and we worked on nothing but strategy. His score improved by three points. This was far from a typical situation, but it is illustrative of why I place so much emphasis on strategies. Because I believe that strategies are so important and I want my students' strategies to be automatic by the time they take their tests, I start with teaching strategies to all of my students. Once a student has solid strategy in place, we then focus on the two other pillars, but strategy is at the core of my work with my students. Click here to read about the second pillar for success on the SAT or ACT.  At most colleges, SAT or ACT scores are important components of their admission criteria. Colleges tend to be opaque about exactly how much weight they give to SAT and ACT scores, and the importance of them varies greatly between colleges. However, for the sake of illustration, let's assume that colleges weight SAT and ACT scores as about a third of their admission criteria. Though this is an assumption made for illustrative purposes, my experience is that this is probably a fairly accurate assumption on average. Given the weight given to SAT and ACT scores in admission criteria, studying for the SAT or ACT is an extremely good use of students' time if they want to be accepted into their top choice colleges. Let's suppose a student does two hours of homework for school on five nights each week. Realistically, many serious students do much more work than this but we'll use this number for our estimate. Most high schools have 36 weeks of school per year. (2 hours of homework/night) x (5 nights/week) x (36 weeks/school year) = 360 hours of homework per school year All states require that students spend at least 1000 hours in the classroom per school year. Some states require more hours than this per year, but let's use the 1000 hours. This means that in just one year of school, a student who averages only two hours of homework per night will spend 360 hours doing homework for school and 1000 hours in school, for a total of 1360 hours spent on school work. In a sense, how well a student does during these 1360 hours is represented by his or her GPA, which is another important criterion for admission to college. Let’s look at how much time a student might spend studying for the SAT or ACT. My recommendation to students who want to see a significant improvement in their SAT or ACT scores is that they do a 90 minute tutoring session with me weekly for four months and do three hours of homework on their own each week. That's a total of four and a half hours per week spent on SAT or ACT preparation for sixteen weeks. (4.5 hours of SAT or ACT studying/week) x (16 weeks) = 72 hours of SAT or ACT studying in total (Some serious students certainly work with me for longer than four months or do more work per week than this and a few of my students work with me for a much shorter time, but four months of working together weekly is about average for my students.) Let's review these numbers. My average recommendation is that students spend a lifetime total of 72 hours studying for the ACT or SAT, and these 72 hours of work will determine their scores that make up a third of their admission criteria. Students who do two hours of homework per night spend 1360 hours on their schoolwork each year, and this makes up less than two thirds of their admission criteria via their GPA. Let’s recap once more: 72 lifetime hours for 1/3 of admission criteria for SAT or ACT. 1360 hours per year for less than 2/3 of admission criteria. Never mind that many students do much more than two hours of homework per night or that these 1360 hours on schoolwork are spent each year for several years or that some schools have more than 1000 instructional hours per year or that application essays and other factors such as sports and volunteering are considered by admission committees in the two thirds of admission criteria that we attributed to GPA. Given all those factors, the calculation that we have done is probably an extremely cautious estimate of how much more impact studying for the SAT or ACT has on an hour-for-hour basis compared to doing homework. Whether a student works with a tutor or not and even if a student is going to spend less time studying than I recommend, any time spent studying for the SAT or ACT is time extremely well spent for anybody with serious college aspirations. In fact, time spent studying for the SAT or ACT has a bigger return on investment than anything else students can do in efforts to get accepted into colleges.  I have a student who I would describe as brilliant. When this student gets a question incorrect, he regularly declares emphatically, “Oh, I'm so stupid!!!” Every time I hear this, I ask, “Do you really believe that? Is that the message that you want to be telling yourself?” I hear many other such exclamations or self-deprecating explanations from my students. “I can't do algebra.” “I'm just not good at taking tests.” “I'm lazy.” “All my friends do so much better on the ACT than I do!” We all tell ourselves stories about ourselves. Our minds use language to explain to ourselves who we are and why things are the way that they are. However, we can learn to notice the stories that we tell ourselves, and we can even choose the stories that we tell ourselves. One possible and well-known way of changing our stories is with affirmations; for example, someone might tell themselves, “I am a great test-taker. I am a great test-taker.” Some people tell me that affirmations work well for them. However, because affirmations are a way of convincing ourselves of something that parts of ourselves may not believe and may not even be true, I prefer an approach that is grounded in assessing the accuracy of our stories and changing them to be more realistic and action-based. I teach my students a “cognitive-behavioral” approach to this. “Oh, I'm so stupid!” might become “I made a mistake, and I think that I'm capable of solving this question correctly, so I feel frustrated with myself. Whether I got this specific question correct or not doesn’t actually mean much about my intelligence.” “I can't do algebra” might become “I have some holes in my algebra knowledge, and I haven't yet learned it as well as I want to learn it, but I'm practicing a lot so that I get better at it.” “I'm just not good at taking tests” could be turned into “I'm spending a lot of time studying and working to improve how I do on the SAT, and I believe that taking the SAT is a learnable skill because my score has already improved.” “I'm lazy” could become “In the past, I often haven't done very much work, but there have also been times that I have done my work. I'm going to make choices in order to do my homework more often.” “All my friends do so much better on the ACT than I do!” could become “It doesn't matter how my friends do on the ACT because I only need to do well enough to get accepted into college. I'm just focusing on practicing my strategies and doing the best I can in each moment.” I want to be clear that my recommendation to be conscious and choiceful about the stories that we tell ourselves is something that I recommend in SUPPORT of doing the real and hard work necessary to achieve improvement on the SAT or ACT or whatever else we are working towards. Trying to achieve something simply through affirmations or changing our thinking might be called magical thinking, and that is not at all what I am recommending. If students change their stories about themselves and consistently choose to take the actions necessary to make their new stories true, by the time their tests are over, they might discover that not only did they achieve the scores they were hoping for but they also became a version of themselves with more positive stories in general. They might even feel happier and more confident, with their great scores or without. I admit it. I am a perfectionist. My default is to want for everything that I do to be flawless, beyond criticism. A deep part of my psyche expects that of myself, and I am sometimes hard on myself if I don't meet my own virtually impossible standards.

I really empathize with my students who approach the SAT or ACT as perfectionists. Unfortunately, perfectionism doesn't work well at all on standardized tests. (I could make a strong argument that perfectionism doesn't work well for much of anything in life and is very unhealthy in general, but I'll stay focused on the topic at hand.) Many of the strategies that I teach are geared toward using every moment during the test in an optimal way to get as many points as possible. Often, succeeding at getting a great score means being willing to let go of getting a perfect score. Hanging on to the hope of a perfect score and not being willing to let go of questions in order to answer everything else on the test well is a great formula for an extremely disappointing score and panic setting in as time runs out with unanswered questions remaining. Several years ago, I had a student who had improved a lot over the time we had worked together, was scoring very high on SAT practice tests, and had really mastered the strategies that I had taught her. She, her parents, and I all considered her to be well prepared to score well. Then, when she was doing the real test, perfectionism took hold of her. She wanted a perfect score, not merely a great one. She couldn’t let any questions go. She couldn’t skip anything. She forgot or ignored all of her strategies. As she wasted precious minutes on a couple of questions that she was unlikely to get correct in any case, she fell behind. She became more anxious and even ceased to think clearly. How well do you think she did on this SAT? Fortunately, she was still in her junior year at this point and was able to take the SAT again. After more work together, on the subsequent sitting she was able to let go of perfectionism, use her strategies effectively, and score extremely well. I emphasize to all of my students in the weeks and days before their tests: do on the real test exactly as you have been practicing. It is working for you. You know how to get a great score by doing what you have been doing on practice tests. Perfectionism is the greatest enemy of great.  Climbing the stairs of the Eiffel Tower is easy compared to becoming fluent in French. Climbing the stairs of the Eiffel Tower is easy compared to becoming fluent in French. Do What You Value, Not What You Want My wife grew up in Paris, and French is her first language. Her English is excellent though, and we communicate with each other primarily in English. Every year, we spend a couple of weeks in Paris visiting her family and friends. Some of her family and most of her friends do not speak English well or even at all. Because I really want to have good relationships with my wife’s family and because I eventually want to be able to speak with my wife fluently in her native language, I take French lessons twice a week. At this point, I would consider myself conversationally functional but not yet fluent. I generally do well in one-on-one conversations, but put me in a group where people are making jokes or there are multiple conversations happening around the table, and I rapidly become lost. I find studying a language to be a slow, laborious process. I misunderstand things that people say. I forget whether words are masculine or feminine and often guess incorrectly when I speak. I forget how to say words that I know I have known in the past. There are a couple of grammatical concepts that I understand theoretically, but I struggle to integrate them when I speak. I sometimes make the same mistake again after my French teacher has previously corrected me on the exact same mistake. Sometimes, I enjoy my French lessons. I genuinely enjoy learning and being challenged. I consider my French teacher to be excellent. Other times though, I have to admit that I find studying French and taking lesson after lesson to be frustratingly slow. I often wonder if I will ever become as good at French as I would like to be. I have so much more to learn to become truly fluent that I sometimes feel overwhelmed. Occasionally, when I utterly fail to communicate the nuance of something that I want to communicate, I feel childish and silly. As someone who found graduate-level engineering math courses easy, I find it humbling to realize how long it takes me to learn a new language. I imagine that many of my students studying for the SAT and ACT have similar feelings about their ACT or SAT test preparations as I do about learning French. I sometimes hear my students make comments such as: “I knew how to do that. I don’t know why I missed it again.” “I know I learned this before, but I forget.” “I don’t even understand what this question is asking.” If learning a new language is difficult and often frustrating for me, why do I do it? Certainly, I would often prefer to go for a walk or read a book (in English) or spend time with my wife (talking in English) than study French. If studying for the SAT or ACT is difficult, laborious, and frustrating, why do my students do it? I imagine that many of them would prefer to hang out with their friends, play video games, watch TV, or do sports. My answer as to why I choose to study French is that even though there might be things that I want to do more in a given moment, I value learning French more than I do following my present-moment wants. I value having a good relationship with my wife’s family. I value being able to communicate with them. I value being able to communicate with my wife in her native language. I value being socially functional when we make our annual trip to Paris. By choosing to spend time studying French, I am placing more value on all of these reasons than I am in doing what I might whimsically want to do from moment to moment. The vast majority of my students do all of the homework that I assign them and work very hard to prepare for the SAT or ACT. Whether they are explicitly aware of this or not, the reason that they choose to spend time studying rather than to do something more enjoyable and easier in-the-moment is because they too value something more highly than their present-moment, whimsical wants. What it is that they value highly differs greatly between students. Some want to have a specific career, such as becoming a medical doctor. Some want choice and freedom. Some want prestige. Some feel competitive. Some want to make a lot of money. Some want to have a positive impact in the world and want to prepare themselves for such work. Regardless of what my students value, I find that it is those who are most able to make choices based upon what they value rather than their present-moment wants who improve the most and do the best on the ACT and SAT. Of course, it is also extremely important to spend time with those we care about, socialize, and do the things that we enjoy, but I believe that doing these because we value them and are intentionally choosing to do them creates a richer, more balanced life than following our whimsical wants of the present moment. In fact, I believe that consistently choosing to act in alignment with what one values rather than reacting to moment-to-moment desires is a key not only to improving and succeeding on the ACT and SAT, but also to living a rich and rewarding life. “I'm not sure how to start this question. I hate logarithms. I don't think I'm doing very well on this section. I’ve already skipped too many questions. I'm going to get a bad score again. I'm not going to get into the college that I want to go to. My parents are going to be so disappointed. My friends all do better on this test than I do. I must not be very smart.”

Many of my students share with me that they often have internal dialogues such as this while they take the SAT or ACT. Other students simply feel anxiety, frustration, or even despair as they stare at a difficult question, even if there isn’t a lot of internal dialog. On tests where a couple of moments wasted can be the difference between a great score and a mediocre score, noticing these moments just as they begin to arise and dealing with them effectively is imperative in order to achieve a great score. Additionally, lingering with despairing thoughts or emotions can fuel more anxiety, more frustration, and more despair, which can turn into a downward spiral as a student proceeds with the test. One of the first test-taking strategies that I teach my students is to notice their thoughts and their emotions as indications of what they should do on a question. I repeat this to my students until they have integrated it: “Are you telling yourself a story? Noticing that you’re having thoughts about a question that have nothing to do with the question? Having an emotion about a question? Simply not making good progress on a question? Noticing any of those is a victory in itself, and staying on a question while any of these is happening isn't a good use of your time. Guess and let it go (for almost everyone on the ACT) or skip it and come back to it (for the SAT and those scoring 34 and up on that section of the ACT).” The faster students notice that they are not using the present moment in an effective ways to maximize their scores as they answer questions, the faster they can make good choices to use their time effectively and maintain positive and productive states of mind during the test. I teach this very early in my work with students because it can take time to learn to do this well. As well as working on this technique when they do practice sections of the SAT or ACT for homework, I also recommend that my students practice noticing their emotions and thoughts as they arise throughout their days in order to practice and solidify these skills so that it becomes second-nature to them by test day. I talk about this skill with my students as self-awareness, the ability to notice emotions and thoughts and make choices without being consumed by or even identifying with the emotion or thought. As valuable as I consider self-awareness to be for the purpose of the SAT and ACT, I also believe that it is one of the most valuable skills that people can learn for all aspects of their lives. It is an essential skill in order to have a high level of emotional intelligence, to lead people, to build effective working relationships, to have deep intimate relationships, and to generally have a fulfilling life. While everything that I teach and do with my students in every session is chosen for the purpose of maximizing their SAT and ACT scores, I do hope and believe that the majority of my students learn many things from working with me that will continue to benefit them long after they have taken their tests. If I could choose only one thing that my students learn and carry forward into their lives though, without hesitation I would choose for them this self-awareness. |

To discuss your SAT or ACT coaching needs, contact Inspired Test Prep by phone at 206-395-6676 or email at [email protected].

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed